Players usually remain safe and separate from the games they are playing. They are free to wreak havoc and violence in their digital world with no consequences. It’s a safety barrier that creates a comfortable level of escapism that most games share. Shatter that safety barrier and you create a sense of immersion that can be powerful, emotional, and sometimes unsettling.

This is called breaking the 4th wall, and every game does it to some extent. The player is usually addressed directly at some point, either during a tutorial or in a thank you after the end credits. But the following games take it to the next level, integrating the 4th wall break into their core mechanics and narrative. If you are in the mood for your game to get a little meta, try one of these titles out.

Honorable Mentions

I’ve tried to limit this list to games that play with the 4th wall throughout their entirety, leaving out singular gimmicks and jokes. That being said, some of these gimmicks are pretty entertaining. Batman: Arkham Asylum took advantage of the player’s fear of the Red Ring of Death by creating a false glitch that boots the game into an unwinnable scenario. X-Men for the Sega Genesis actually required you to reset the console in order to get past the Danger Room. Old Lucas Arts games loved to crack jokes about the video game market or the ineptitude of the player.

I’ve tried to limit this list to games that play with the 4th wall throughout their entirety, leaving out singular gimmicks and jokes. That being said, some of these gimmicks are pretty entertaining. Batman: Arkham Asylum took advantage of the player’s fear of the Red Ring of Death by creating a false glitch that boots the game into an unwinnable scenario. X-Men for the Sega Genesis actually required you to reset the console in order to get past the Danger Room. Old Lucas Arts games loved to crack jokes about the video game market or the ineptitude of the player.

There are literally hundreds of great examples of 4th wall breaking gimmicks and I’d be here forever if I tried to list them all, so here are ten of the very best.

StarTropics

OK, OK, you got me. StarTropics did break the 4th wall as a gimmick, specifically as a method of primitive DRM. But the gimmick was so innovative it deserved a spot on this list nonetheless.

OK, OK, you got me. StarTropics did break the 4th wall as a gimmick, specifically as a method of primitive DRM. But the gimmick was so innovative it deserved a spot on this list nonetheless.

Before the game begins, the player finds a real paper letter inside their game box. The letter outlines the plot and tells the player where to go at the start of the game. From then on, the game plays as normal until you receive a message asking you to dip the letter in water. Players have usually forgotten about the letter at this point, and the “Eureka!” moment came when you realized that you needed to dip it in actual physical water. Doing so revealed a code, which was used later in the game and gave directions on where to go next.

It was a fantastic way to draw the player into the action, and it successfully kept renters and pirates from actually completing the game. Its only flaw was that it could only be done once, giving it far less impact for anyone who bought the game second hand. Nowadays, retro gamers will have to look up the code on the internet, or use the Wii U’s virtual manual to dip a virtual letter into virtual water…but that’s not quite the same.

The Mother Series

The Mother series loves to make the player a part of its narrative. Mother 2 (known as Earthbound here in the states) and Mother 3 asked for the player’s name at a random point in the middle of the game. They then play for hours like any other JRPG, in the hopes that the player will forget. But this small piece of personal information totally flips the narrative on its head when the time comes for the climax.

The Mother series loves to make the player a part of its narrative. Mother 2 (known as Earthbound here in the states) and Mother 3 asked for the player’s name at a random point in the middle of the game. They then play for hours like any other JRPG, in the hopes that the player will forget. But this small piece of personal information totally flips the narrative on its head when the time comes for the climax.

In Mother 2, the only thing that could defeat a primordial force of evil was something even more powerful – something that existed only outside of the game – you the player. The death animation for the final boss is modeled after a television getting overwhelmed by static before turning off. Some interpret the ending as implying the only way to defeat this evil was to exert your power as a player outside the game world and “turn the game off.”

In Mother 3, the morality of the protagonist and antagonist play a huge role in the narrative. Their actions were said to determine whether a powerful magical being would bring the world salvation or destruction. It’s only at the end of the game that you realize that you are that being, and the salvation and destruction of the world is tied to how you interpret the game’s ending.

Metal Gear Solid

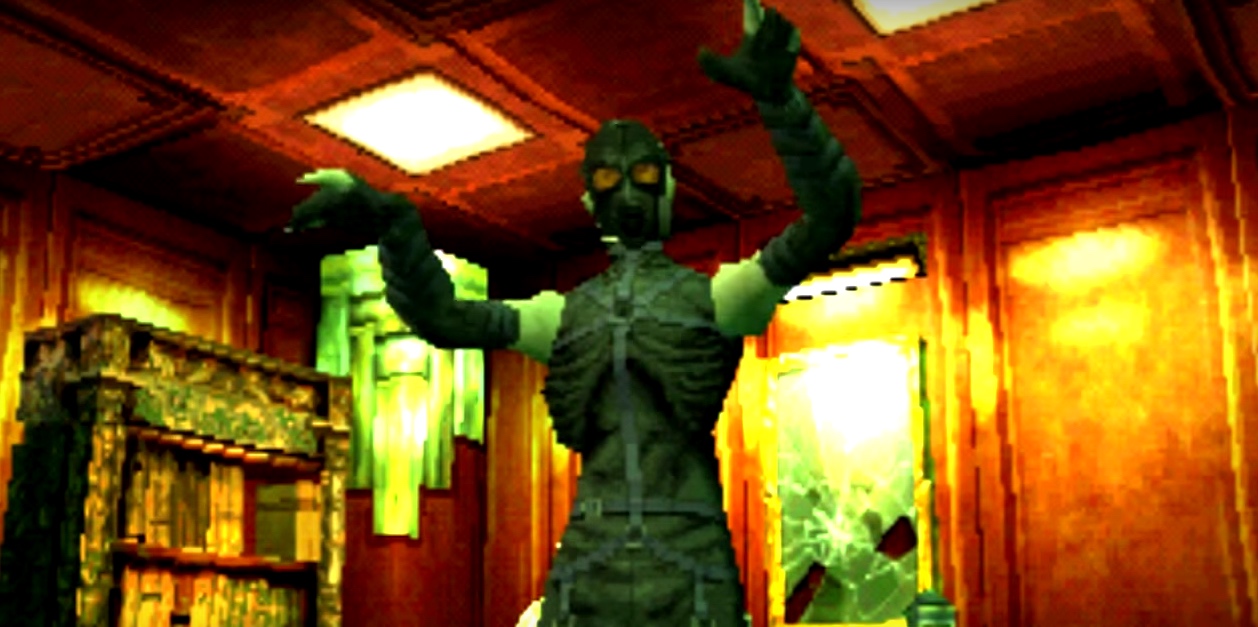

The original Metal Gear Solid probably has the most iconic 4th wall break in the battle with Psycho Mantis. This villain opened up his boss battle by predicting the player’s video game preferences (done by reading files off their memory card). He could only be defeated by switching the port the controller was plugged into.

The original Metal Gear Solid probably has the most iconic 4th wall break in the battle with Psycho Mantis. This villain opened up his boss battle by predicting the player’s video game preferences (done by reading files off their memory card). He could only be defeated by switching the port the controller was plugged into.

But this was hardly the only time that Metal Gear Solid screwed with the 4th wall. An important codec was printed on the back of the Metal Gear Solid CD case. The identity of the main character of The Phantom Pain is suspect when it appears as if he may be you, and you may be playing Metal Gear 2 for the MSX. Metal Gear Solid 2 is completely self-aware of the fact that it is a video game. It’s basically a central plot point! Look hard enough and you’ll find a 4th wall break in nearly every title in the series.

Spec Ops: The Line

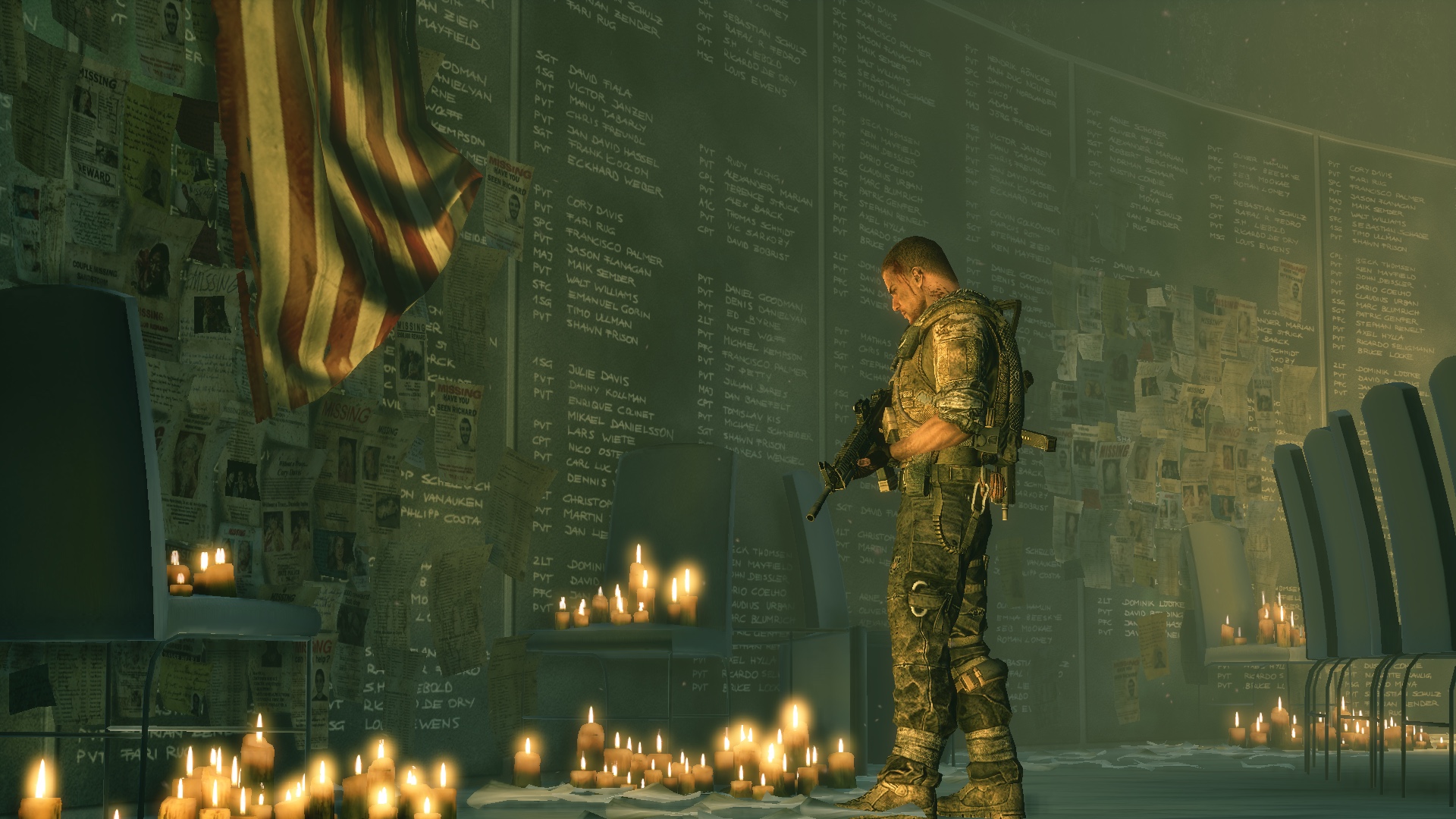

Spec Ops: The Line starts off like every other military shooter. A righteous American military hero has to fly to a foreign country, shoot up the bad guys, and save the day. But as the game goes on you begin to feel not so righteous. Your actions feel less like military heroics and more like wanton violence. Set-pieces feel staged, repetitive, and unnecessary, meant only to fuel your thirst for guns and military technology. NPCs criticize you for being insane and chasing a phantom enemy beyond all reason or sound military strategy. By the end of the game, even the loading screens are commenting on what a horrible person you are. It’s then that you realize that it wasn’t the main character that was being condemned – it was the player, for reveling in the horrors of war like a game.

Spec Ops: The Line starts off like every other military shooter. A righteous American military hero has to fly to a foreign country, shoot up the bad guys, and save the day. But as the game goes on you begin to feel not so righteous. Your actions feel less like military heroics and more like wanton violence. Set-pieces feel staged, repetitive, and unnecessary, meant only to fuel your thirst for guns and military technology. NPCs criticize you for being insane and chasing a phantom enemy beyond all reason or sound military strategy. By the end of the game, even the loading screens are commenting on what a horrible person you are. It’s then that you realize that it wasn’t the main character that was being condemned – it was the player, for reveling in the horrors of war like a game.

Eternal Darkness

Eternal Darkness didn’t only break the 4th wall, it quantified it! The game, loosely based on Lovecraftian horror, had you manage a “sanity” meter. As your characters were exposed to the creeping horrors from beyond, their sanity dropped causing them to see things that weren’t really there. Slight sanity damage made you see enemies that didn’t exist or walk down hallways that never ended. Bigger sanity hits made you think that the game crashed or deleted your save file. It was a fantastic way to bring horror and insanity out of the game and into your living room, and it remains a horror classic to this day because of its innovative 4th wall breaking mechanics.

Eternal Darkness didn’t only break the 4th wall, it quantified it! The game, loosely based on Lovecraftian horror, had you manage a “sanity” meter. As your characters were exposed to the creeping horrors from beyond, their sanity dropped causing them to see things that weren’t really there. Slight sanity damage made you see enemies that didn’t exist or walk down hallways that never ended. Bigger sanity hits made you think that the game crashed or deleted your save file. It was a fantastic way to bring horror and insanity out of the game and into your living room, and it remains a horror classic to this day because of its innovative 4th wall breaking mechanics.

Deadpool

Most of the games on this list break the 4th wall to make a statement or elicit an emotion. Deadpool, however, broke the 4th wall for the lolz. The titular hero interacts with the narrator, threatens the game designer, edits his own game’s script, and repeatedly addresses the player throughout the game. The 4th wall is basically non-existent. I’d like to say that there was some greater purpose to all of these 4th wall breaks, but there wasn’t. It’s just Deadpool being Deadpool, and it’s hilarious.

Most of the games on this list break the 4th wall to make a statement or elicit an emotion. Deadpool, however, broke the 4th wall for the lolz. The titular hero interacts with the narrator, threatens the game designer, edits his own game’s script, and repeatedly addresses the player throughout the game. The 4th wall is basically non-existent. I’d like to say that there was some greater purpose to all of these 4th wall breaks, but there wasn’t. It’s just Deadpool being Deadpool, and it’s hilarious.

The Stanley Parable

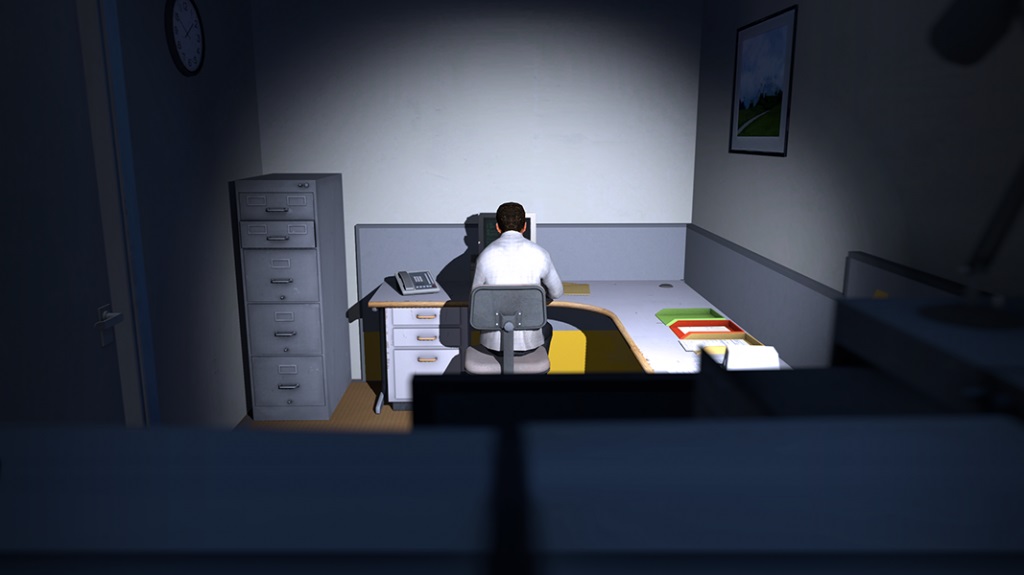

The Stanley Parable’s central game mechanic was breaking the 4th wall. All you (and by extension Stanley) could do was walk and sometimes interact with the environment. The game is all about choosing whether or not you do what the narrator tells you to. In the beginning, this causes the narrator and Stanley to get into some humorous fights, but as the game goes on the plot starts to get meta. At one point, you walk through a museum about the very game you are playing while a new narrator narrates the actions of the original narrator. Another path detaches you from Stanley and makes you watch on as a ghostly presence hovering above him, powerless to do anything. At one point the game begs you to shut it off, professing that it’s the only way to win. It’s a fantastic reflection on the reader’s effect on a narrative, done as only a video game can.

The Stanley Parable’s central game mechanic was breaking the 4th wall. All you (and by extension Stanley) could do was walk and sometimes interact with the environment. The game is all about choosing whether or not you do what the narrator tells you to. In the beginning, this causes the narrator and Stanley to get into some humorous fights, but as the game goes on the plot starts to get meta. At one point, you walk through a museum about the very game you are playing while a new narrator narrates the actions of the original narrator. Another path detaches you from Stanley and makes you watch on as a ghostly presence hovering above him, powerless to do anything. At one point the game begs you to shut it off, professing that it’s the only way to win. It’s a fantastic reflection on the reader’s effect on a narrative, done as only a video game can.

The Beginner’s Guide

If The Stanley Parable was a commentary on the reader’s role in relation to a story, The Beginner’s Guide is a commentary on the reader’s role in relation to an author. It’s essentially a game about playing games. The narrator, Davey Wreden (the creator of The Stanley Parable), guides you through a number of independent games made by Coda, an old friend of his.

If The Stanley Parable was a commentary on the reader’s role in relation to a story, The Beginner’s Guide is a commentary on the reader’s role in relation to an author. It’s essentially a game about playing games. The narrator, Davey Wreden (the creator of The Stanley Parable), guides you through a number of independent games made by Coda, an old friend of his.

As you play these games, Davey analyzes them for you. This causes you to apply the same analysis to The Beginner’s Guide and, by extension, Davey. By the end of the game, Davey’s pretext of analysis breaks down, and he questions whether he was analyzing himself rather than Coda all along. This begs the question, were you really analyzing The Beginner’s Guide this whole time, or were you analyzing yourself, just like Davey was?

Pony Island

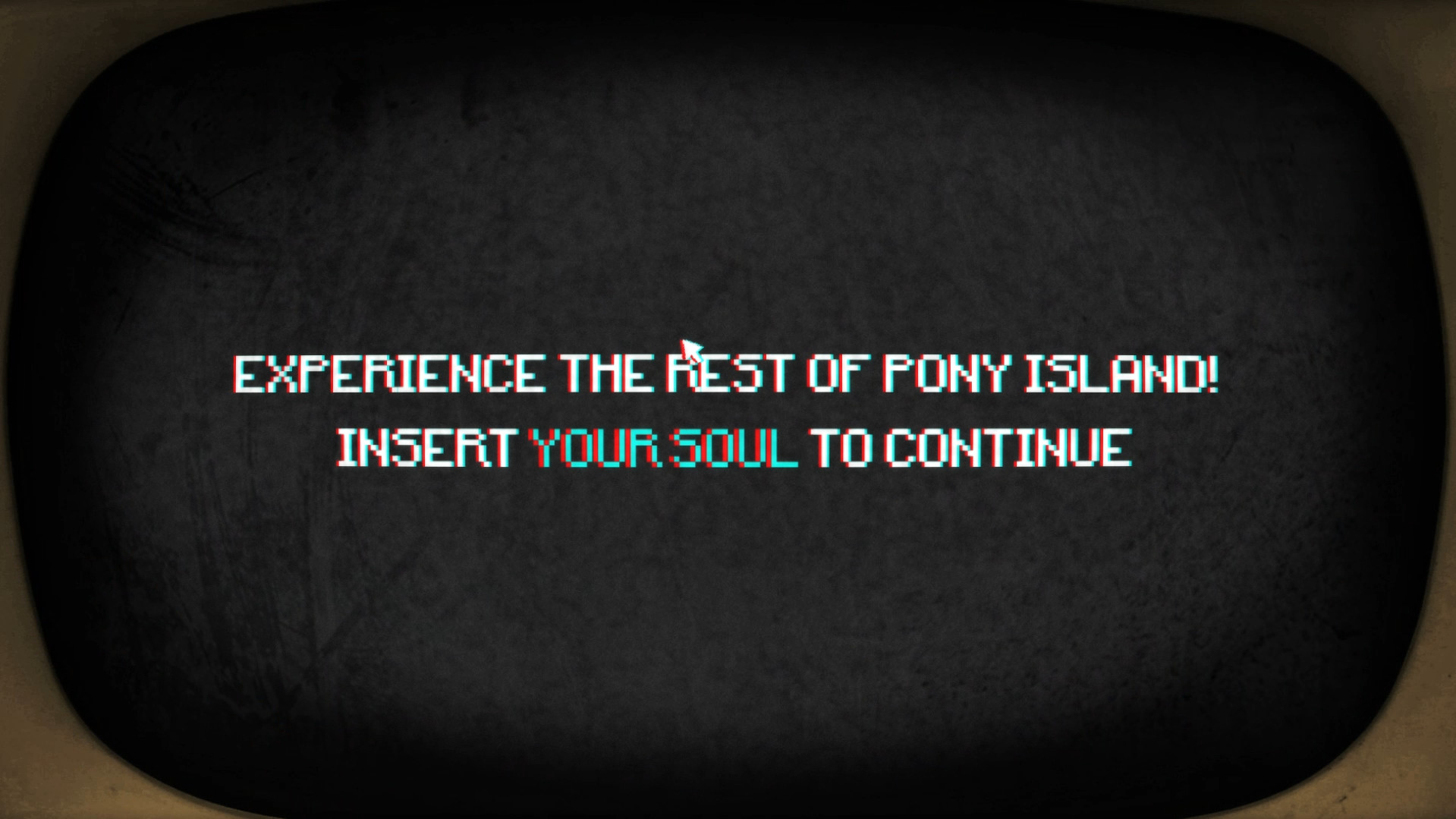

Pony Island is another game within a game, but with a simultaneously more comedic and more sinister tone. Here you act as an arcade patron playing a game called Pony Island. But this cutesy infinite runner is far more evil than it originally lets on. Soon, you find yourself ensnared in a battle for your very soul with malicious demonic files that have taken over your computer. Some will even use the Steam interface to screw with you, making entities from inside the game contact you outside the game. To win, you will have to overcome the game’s code, your own computer system, and Satan himself!

Pony Island is another game within a game, but with a simultaneously more comedic and more sinister tone. Here you act as an arcade patron playing a game called Pony Island. But this cutesy infinite runner is far more evil than it originally lets on. Soon, you find yourself ensnared in a battle for your very soul with malicious demonic files that have taken over your computer. Some will even use the Steam interface to screw with you, making entities from inside the game contact you outside the game. To win, you will have to overcome the game’s code, your own computer system, and Satan himself!

And ponies…there’s also ponies.

Read our review of Pony Island for more on this special, special game.

Undertale

Finally we have the best example of 4th wall breakage, and my pick for Game of the Year 2015: Undertale. A shallow reading would lead you to believe that the game is merely about a child trying to find their way out of an underground world of monsters. However, a deep reading reveals much more than that.

Undertale is yet another game about morality and choice, but not just the choices you make when playing. Rather, it criticizes every choice you have made in every game you have ever played. It asks you whether or not you treated the characters in these game worlds like people, or like playthings. It makes you wonder whether or not this is how an all-powerful God or deity might see us. It goes to great lengths to break that pattern, making you fall in love with the rich and diverse characters that occupy its world.

And then it taunts you. You see, the only way to experience the whole story is to see every ending. But one ending asks you to ruthlessly murder every character you have come to know and love. There, you are given your final moral choice. Will you abandon perfectionism and completionism for the sake of ethics?

If you heed Undertale’s advice and stop playing, you’ll inevitably feel the itch of completionism gnawing at the back of your mind. “But I just want to see the rest of the game,” you’ll tell yourself, just as the game predicted you would. It warns you that you’ll give in to your murderous urges simply out of boredom, which is exactly how you’ll feel. The less you play the game, the more it becomes “just a game” to you, wiping the moral and ethical questions clean.

And so the final choice you have to make is: will you give in and play the game again? This is one game where, truly, the only way to win is to stop playing.